2023 Research Misconduct News

This page offers news-worthy topics for the Responsible Conduct of Research and Research Misconduct. Note: Due to the nature of web page evolution, some links may be broken.

| January | February | March | April | May | June |

| July | August | September | October | November | December |

Harvard president to update dissertation as House probes plagiarism claims

December 21, 2023

AXIOS

Rebecca Falconer

A Republican-led U.S. House committee is expanding its investigation into Harvard to include allegations of plagiarism against the university's president, Claudine Gay.

Why it matters: Harvard last week cleared Gay of "research misconduct" after plagiarism allegations emerged, but Education and Workforce Committee Chair Virginia Foxx (R-N.C.) announced Wednesday that the panel had begun a review of Harvard's handling of the allegations that she said were "credible."

The latest: Gay will submit updates to her 1997 dissertation, which will add quotations and citations, a university spokesperson said in a statement provided to Axios on Thursday.

Silent, yet indispensable

December 11, 2023

Research Information

Andrea Chiarelli

Andrea Chiarelli explains how identifiers, metadata and shared infrastructures bolster research integrity

With the Retraction Watch database hitting almost 50,000 items and an ever-growing number of high-profile research misconduct cases, questions around the veracity of published research findings are becoming uncomfortably common. Verifying the accuracy of published research is a meticulous and rigorous process. Today, this requires painstaking and mostly manual work, although technology is rapidly coming to the rescue: following decades of digital research infrastructure development, we can start to imagine a future where humans and machines can work together to validate the public record and help corroborate its trustworthiness.

Leading scholarly database listed hundreds of papers from ‘hijacked’ journals

Scopus is giving suspect, non–peer-reviewed papers unwarranted legitimacy, researchers say

December 5, 2023

Science

Jeffrey Brainard

Scopus, a widely used database of scientific papers operated by publishing giant Elsevier, plays an important role as an arbiter of scholarly legitimacy, with many institutions around the world expecting their researchers to publish in journals indexed on the platform. But users beware, a new study warns. As of September, the database listed 67 “hijacked” journals—legitimate publications taken over by unscrupulous operators to make an illicit profit by charging authors fees of up to $1000 per paper. For some of those journals, Scopus had listed hundreds of papers.

These ersatz publications represent a tiny fraction of the more than 26,000 active, peer-reviewed journals indexed in Scopus. Still, says Anna Abalkina, who authored the study, published on 27 November in the Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, any number above zero is troubling because it means the scholarly record is being corrupted. Some of the work published in hijacked journals may be legitimate, says Abalkina, a social scientist at the Free University of Berlin. But previous analyses have found that many papers in hijacked journals were plagiarized, fabricated, or published without peer review.

Is AI leading to a reproducibility crisis in science?

Scientists worry that ill-informed use of artificial intelligence is driving a deluge of unreliable or useless research.

December 5, 2023

Nature

Philip Ball

During the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2020, testing kits for the viral infection were scant in some countries. So the idea of diagnosing infection with a medical technique that was already widespread — chest X-rays — sounded appealing. Although the human eye can’t reliably discern differences between infected and non-infected individuals, a team in India reported that artificial intelligence (AI) could do it, using machine learning to analyse a set of X-ray images1.

The paper — one of dozens of studies on the idea — has been cited more than 900 times. But the following September, computer scientists Sanchari Dhar and Lior Shamir at Kansas State University in Manhattan took a closer look2. They trained a machine-learning algorithm on the same images, but used only blank background sections that showed no body parts at all. Yet their AI could still pick out COVID-19 cases at well above chance level.

How to Stop Academic Fraudsters

Data fabrication is an old problem. New preventive measures can help.

December 4, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Alex O. Holcombe

"Hi Alex, this is not credible.”

I’ll never forget that email. It was 2016, and I had been helping psychology researchers design studies that, I hoped, would replicate important and previously published findings. As part of a replication-study initiative that I and the other editors had set up at the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, dozens of labs around the world would collect new data to provide a much larger dataset than that of the original studies.

With the replication crisis in full swing, we knew that data dredging and other inappropriate research practices meant that some of the original studies were unlikely to replicate. But we also thought our wide-scale replication effort would confirm some important findings. Upon receiving the “this is not credible” message, however, I began to be haunted by another possibility — that at least one of those landmark studies was a fraud.

Exploring Policies to Prevent "Passing the Harasser" in Higher Education

December 2023

National Academies

Serio, T., A. Blamey, L. Rugless, V. R. Sides, M. Sortman, H. Vatti, and Q. Williams. 2023. Exploring Policies to Prevent "Passing the Harasser" in Higher Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27265.

One troubling aspect of sexual harassment by faculty is the ability of these individuals to quietly move on to new academic positions at other institutions of higher education (IHEs) without the disclosure of their behavior. This practice is known as passing the harasser, and is exacerbated by a general lack of transparency about findings of sexual harassment in higher education. The ramifications of passing the harasser include not only failing to hold harassers accountable for their actions but also reinforcing an institutional climate in which sexual harassment is perceived as tolerated.

The Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine brings together academic and research institutions and key stakeholders to work toward targeted, collective action on addressing and preventing sexual harassment across all disciplines and among all people in higher education. The Action Collaborative includes four working groups (Prevention, Response, Remediation, and Evaluation) that identify topics in need of research, gather information, and publish resources for the higher education community.

Case Study in Research Integrity: This Application Feels Familiar

November 21, 2023

extramural NEXUS

Mike Lauer

Imagine you are reviewing an application for an NIH study section meeting, and you come across an application that seems just a bit too familiar. The scientific question falls within your wheelhouse. The methods and strategies seem spot on. And isn’t that how you format your text? In this case study, we will discuss how plagiarism in the grant application process is handled at NIH and remind the research community about the importance of maintaining confidentiality of the peer review process. The scenario presented is based on real-world events, with all names and identifiers removed or changed.

Dr. ABC found themselves in this situation. While serving as a peer reviewer, they were assigned an application containing sections that looked very similar to their own application submitted several years prior. The current application identifies Dr. XYZ as the project’s lead, who also serves as principal investigator on other NIH awards. ABC immediately contacted the NIH Scientific Review Officer overseeing the study section to share their concerns.

Correction is courageous

November 9, 2023

Science

H. Holden Thorp

In a year when disagreements over scientific matters like COVID-19 continue to occupy political discourse, the surfacing of a spate of high-profile research errors is regrettable. It’s crucial that the public trusts science at a time when so many topics—artificial intelligence, climate change, and pandemics—cast shadows of uncertainty on the future. Errors, intentional or not, erode confidence in science. It’s not surprising that science integrity has become a focal point for major institutions in the United States, from the White House to the National Institutes of Health. Evaluating policies on misconduct is essential, but the idea of a scientific ecosystem that is free of errors is an unattainable utopia. However, evolving a more responsive ecosystem is entirely possible, and scientific journals, institutions, and researchers must together move more intentionally in this direction.

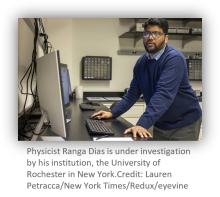

Nature retracts controversial superconductivity paper by embattled physicist

This is the third high-profile retraction for Ranga Dias. Researchers worry the controversy is damaging the field’s reputation.

November 7, 2023

Nature

Davide Castelvecchi

Nature has retracted a controversial paper1 claiming the discovery of a superconductor — a material that carries electrical currents with zero resistance — capable of operating at room temperature and relatively low pressure.

The text of the retraction notice states that it was requested by eight co-authors. “They have expressed the view as researchers who contributed to the work that the published paper does not accurately reflect the provenance of the investigated materials, the experimental measurements undertaken and the data-processing protocols applied,” it says, adding that these co-authors “have concluded that these issues undermine the integrity of the published paper”. (The Nature news team is independent from its journals team.)

How big is science’s fake-paper problem?

An unpublished analysis suggests that there are hundreds of thousands of bogus ‘paper-mill’ articles lurking in the literature.

November 6, 2023

Nature

Richard Van Noorden

The scientific literature is polluted with fake manuscripts churned out by paper mills — businesses that sell bogus work and authorships to researchers who need journal publications for their CVs. But just how large is this paper-mill problem?

An unpublished analysis shared with Nature suggests that over the past two decades, more than 400,000 research articles have been published that show strong textual similarities to known studies produced by paper mills. Around 70,000 of these were published last year alone (see ‘The paper-mill problem’). The analysis estimates that 1.5–2% of all scientific papers published in 2022 closely resemble paper-mill works. Among biology and medicine papers, the rate rises to 3%.

Co-developer of Cassava’s potential Alzheimer’s drug cited for ‘egregious misconduct’

City University of New York’s Hoau-Yan Wang couldn’t provide original data to refute allegations of image manipulation, university says

October 12, 2023

Science

Charles Piller

Cassava Sciences, a biotech company whose work on the experimental Alzheimer’s drug simufilam has been heavily criticized and is the subject of ongoing federal probes, has suffered another blow. A much-anticipated investigation by the City University of New York has accused neuroscientist Hoau-Yan Wang, a CUNY faculty member and longtime Cassava collaborator, of scientific misconduct involving 20 research papers. Many provided key support for simufilam’s jump from the lab into clinical studies and, given the CUNY report, some scientists are now calling for the two ongoing trials to be suspended.

The investigative committee found numerous signs that images were improperly manipulated, for example in a 2012 paper in The Journal of Neuroscience that suggested simufilam can blunt the pathological effects of beta amyloid, a protein widely thought to drive Alzheimer’s disease. It also concluded that Lindsay Burns, Cassava’s senior vice president for neuroscience and a co-author on several of the papers, bears primary or partial responsibility for some of the possible misconduct or scientific errors.

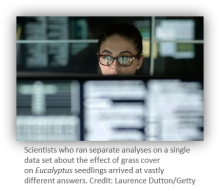

Reproducibility trial: 246 biologists get different results from same data sets

Wide distribution of findings shows how analytical choices drive conclusions.

October 12, 2023

Nature

Anil Oza

In a massive exercise to examine reproducibility, more than 200 biologists analysed the same sets of ecological data — and got widely divergent results. The first sweeping study1 of its kind in ecology demonstrates how much results in the field can vary, not because of differences in the environment, but because of scientists’ analytical choices.

“There can be a tendency to treat individual papers’ findings as definitive,” says Hannah Fraser, an ecology meta researcher at the University of Melbourne in Australia and a co-author of the study. But the results show that “we really can’t be relying on any individual result or any individual study to tell us the whole story”.

How early-career researchers can learn to trust negative data: five simple steps

It took PhD student Jelle van der Hilst some time to realize that getting data is easy; working out whether they’re useful is harder.

September 11, 2023

Nature

Jelle van der Hilst

When I decided to pursue a PhD five years ago, I was ready to face the challenges of finding the right laboratory, securing funding and designing the perfect project. I knew the analysis and interpretation of results would produce hard questions and sleepless nights, and I dutifully reserved some mental capacity for worrying about the eventual task of thesis writing. Once I’d joined a lab in the bioengineering department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, where I study the self-assembling proteins that form powerful lenses in the eyes of squid, I quickly realized that getting data would be much less challenging than interpreting them — or trusting them.

For example, I once spent several weeks trying to measure the size of protein particles I was working with in an effort to determine whether they self-assembled into larger aggregates. I applied the same technique to the same protein under the same conditions and got three vastly different results over three days — each supporting a different hypothesis. Data are data, I thought, until I had a pile of them, and realized I had no idea whether any of them were meaningful.

A perfectly executed experiment might produce data that are utterly inconclusive, or you might get what look like beautiful, exciting data from a botched experiment. How can you tell the difference? Below are some tips on how I learnt to distinguish between the two.

Scientific sleuths spot dishonest ChatGPT use in papers

Manuscripts that don’t disclose AI assistance are slipping past peer reviewers.

September 8, 2023

Nature

Gemma Conroy

On 9 August, the journal Physica Scripta published a paper that aimed to uncover new solutions to a complex mathematical equation1. It seemed genuine, but scientific sleuth Guillaume Cabanac spotted an odd phrase on the manuscript’s third page: ‘Regenerate response’.

How to Review an Academic Journal Article

Michael Tavel Clarke and Faye Halpern recommend an approach that allows those weighing in to act more like mentors than gatekeepers.

September 5, 2023

Inside Higher Ed

Michael Tavel Clarke and Faye Halpern

In the dozen years we have co-edited the journal ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, we have read many external reports supplied by colleagues in our discipline. We have also written peer reviews for other journals ourselves. Throughout those experiences, we have been struck by a peculiar challenge presented by the reader report: the challenge of audience.

Peer reviews are commissioned and read by editors, but they are also sent to the author of the piece being reviewed. Because journal editors are the ones who request reader reports, it’s natural to assume they are the primary audience for your review. However, we would like to propose that you think of the author as your primary audience and write your report accordingly.

Why do we recommend this approach? It allows journals to act more like mentors than gatekeepers.

Is scientific fraud getting worse in chemistry papers?

September 4, 2023

ChemistryWorld

Tom Metcalfe

A study of more than 1200 chemistry retractions over 20 years shows an increase in research fraud.

But independent experts say the number of retractions doesn’t reflect the scale of the problem: many cases of scientific fraud go unnoticed amid the vast ‘firehose’ of papers published in the scientific literature, and some publishers simply ignore complaints.

The lead author of the new study notes the number of retracted chemistry papers increased over 20 years from about 10 to about 100 a year. But ‘retraction growth is not uniform and varies, as massive frauds are only detected incidentally’, says chemistry librarian Yulia Sevryugina of the University of Michigan.

Using the Retraction Watch database, Sevryugina and her co-author identified 1292 retracted articles published in chemistry journals between 2001 and 2021 – roughly 0.06% of chemistry papers published during that time.

Too official to be effective: An empirical examination of unofficial information channel and continued use of retracted articles

September 2023

Research Policy

Volume 52, Issue 7

Haifeng Xu, Yi Ding, Cheng Zhang, Bernard C.Y. Tan

Abstract

Due to the inadequacy of official notices in disseminating retraction information, a significant proportion of retracted articles continue to be cited in the post-retraction period. There are adverse consequences of citing such questionable articles. This study extends the literature on official versus unofficial information channels by examining three key roles that unofficial information channels can play in disseminating retraction information (i.e., providing broader reach for information dissemination, packaging information from different sources, and creating new information) as well as the effects of these roles. An unofficial information channel affords a broader reach for information dissemination, which reduces post-retraction citations. Moreover, according to the information processing theory, different types of additional information (that comes from the ability of an unofficial information channel to package information from different sources or create new information) can moderate such effect. Leveraging on the launch of Retraction Watch (RW), an unofficial information channel for reporting retractions, this study designed a natural experiment and found that reporting retractions on RW significantly reduced post-retraction citations of non-swiftly retracted articles in biomedical sciences. Furthermore, additional author-related and retraction-related information provided on RW enhanced the main effect, whereas additional article-related information provided on RW weakened the main effect.

‘Gagged and blindsided’: how an allegation of research misconduct affected our lab

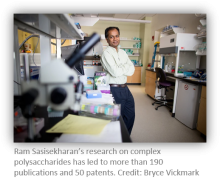

Bioengineer Ram Sasisekharan describes the impact of a four-year investigation by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which ultimately cleared him.

August 25, 2023

Nature

Anne Gulland

In May 2019, a phone call to Ram Sasisekharan from a reporter at The Wall Street Journal triggered a chain of events that stalled the bioengineer’s research, decimated his laboratory group and, he says, left him unable to help find treatments for emerging infectious diseases during a global pandemic.

The journalist had rung Sasisekharan, who works at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, for his comment on an article in the journal mAbs that had been published a few days previously1. The article alleged that Sasisekharan and his co-authors had “an intent to mislead as to the level of originality and significance of the published work”.

No, ChatGPT Can't Be Your New Research Assistant

Just look at what happens when you use it to find sources.

August 23, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Maggie Hicks

Amy Chatfield, an information services librarian for the Norris Medical Library at the University of Southern California, can hunt down and deliver to researchers just about any article, book, or journal, no matter how obscure the topic or far-flung the source.

So she was stumped when she couldn’t locate any of the 35 sources a researcher had asked her colleague to deliver.

Each source included an author, journal, date, and page numbers, and had seemingly legit titles such as “Loan-out corporations for entertainers and athletes: A closer look,” published in the Journal of Legal Tax Research.

Then she started noticing oddities about the sources.

When Scholars Sue Their Accusers

Francesca Gino is the latest. Such litigation rarely succeeds.

August 18, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Adam Marcus and Ivan Oransky

Francesca Gino has made headlines twice since June: once when serious allegations of misconduct involving her work became public, and again when she filed a $25-million lawsuit against her accusers, including Harvard University, where she is a professor at the business school.

The suit itself met with a barrage of criticism from those who worried that, as one scientist put it, it would have a “chilling effect on fraud detection.” A smaller number of people supported the move, saying that Harvard and her accusers had abandoned due process and that they believed in Gino’s integrity.

How the case will play out, of course, remains to be seen. But Gino is hardly the first researcher to sue her critics and her employer when faced with misconduct findings.

New call for joint effort to bolster research integrity

August 17, 2023

Phys.org

Digital Science

Who's responsible for upholding research integrity, mitigating misinformation or disinformation and increasing trust in research? Everyone, even those reporting on research, says a new article published by leading research integrity experts.

In their paper published in the journal Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, Dr. Leslie McIntosh (Vice President Research Integrity, Digital Science) and Ms Cynthia Hudson Vitale (Director, Science Policy and Scholarship, Association of Research Libraries) call for improved policies and worldwide coordination between funding bodies, publishers, academic institutions, scholarly societies, policymakers and the media.

"Scientific reputation requires a coordinated approach across all stakeholders," they write.

How bibliometrics and school rankings reward unreliable science

August 17, 2023

thebmj

Ivan Oransky, Adam Marcus, and Alison Abritis

If we want better science we should start by deflating the importance of citations in promoting, funding, and hiring scientists, say Ivan Oransky and colleagues

How much is a citation worth? $3? $6? $100 000?

Any of those answers is correct, according to back-of-the-envelope calculations over the past few decades.123 The spread between these numbers suggests that none of them is accurate, but it’s inarguable that citations are the coin of the realm in academia.

Bibliometrics and school rankings are largely based on publications and citations. Take the Times Higher Education rankings, for example, in which citations and papers count for more than a third of the total score.4 Or the Shanghai Ranking, 60% of which is determined by publications and highly cited researchers.5 The QS Rankings count citations per faculty as a relatively low 20%.6 But the US News Best Global Universities ranking counts publication and citation related metrics as 60%.7

These rankings are not, to borrow a phrase, merely academic matters. Funding agencies, including many governments, use them to decide where to award grants. Citations are the currency of academic success, but their value also attracts more money and resources to institutions and academics.

BMJ 2023; 382 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p1887 (Published 17 August 2023)

How scientists work to correct the record when there is an error in a paper

Probe of Stanford president shows how people and institutions work to safeguard science

July 31, 2023

The Washington Post

Susan Svrluga and Mark Johnson

Marc Tessier-Lavigne, an internationally known neuroscientist, recently resigned as president of Stanford University after an investigation determined he had failed to correct errors in years-old scientific papers, and that labs he led had an unusual number of instances of manipulated data.

Tessier-Lavigne said he would ask for three papers to be retracted and two corrected, a request the publications say they will honor or review.

A panel of scientific experts — convened as part of an inquiry sparked by reporting in the Stanford Daily — concluded that Tessier-Lavigne did not falsify scientific data or engage in research misconduct and did not find any evidence that he knew of problems in the papers before they were published.

Marc Tessier-Lavigne’s resignation shows what happens when you don’t pay attention to lab culture

July 26, 2023

STAT: First Opinion

C. K. Gunsalus

Last week, Marc Tessier-Lavigne announced that he will resign as president of Stanford over work performed many years ago, in labs at three different institutions. While most of the attention has been focused on the fall from grace of this distinguished scientist, this sad situation carries broader lessons about avoidable outcomes.

A delicately worded sentence in the investigative panel’s report notes that there “may have been” opportunities to “improve laboratory oversight and management” in the Tessier-Lavigne lab. This understated conclusion rests on three elements identified by the panel: multiple people in the lab manipulated data over time, there were “oversights” in correcting the scientific record once discrepancies were called to Tessier-Levigne’s attention, and the lab culture was wanting in key ways.

Stanford’s President Steps Down After Investigation Finds He ‘Failed’ to Correct Mistakes in Papers

July 19, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Francie Diep

Marc Tessier-Lavigne is stepping down as president of Stanford University, after months of intensifying allegations of past research misconduct in his labs and just as the university released the much-anticipated results of an investigation commissioned by the Board of Trustees.

That investigation found that while Tessier-Lavigne hadn’t personally engaged in misconduct, he had “failed to decisively and forthrightly correct mistakes in the scientific record.”

Harvard behavioral scientist faces research fraud allegations

Allegedly falsified data found in already-retracted paper about dishonesty

June 21, 2023

Science

Cathleen O'Grady

Data sleuths say they have found evidence of possible research fraud in several papers by Francesca Gino, a behavioral scientist at Harvard Business School. The publications under scrutiny include a 2012 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) paper on dishonesty that has already been retracted for apparent data fabrication by a different researcher.

“That’s right: Two different people independently faked data for two different studies in a paper about dishonesty,” write behavioral scientists Uri Simonsohn, Joseph Simmons, and Leif Nelson on their blog, Data Colada, where they published the new evidence supporting their allegations.

MIT Exonerates Professor—After 3.5-Year Wait

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology received research misconduct allegations against Ram Sasisekharan in 2019. It didn’t clear his name until this spring.

June 20, 2023

Inside Higher Ed

Ryan Quinn

This spring, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology finally announced it had exonerated Ram Sasisekharan, a biological engineering professor, after a three-and-a-half-year research misconduct investigation.

Sasisekharan has been an MIT professor for nearly 30 years. He claims over 50 patents and says he’s founded six companies.

But he says the allegations and long investigation severely damaged his lab’s work.

A Weird Research-Misconduct Scandal About Dishonesty Just Got Weirder

June 16, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Stephanie M. Lee

Almost two years ago, a famous study about a clever way to prompt honest behavior was retracted due to an ironic revelation: It relied on fraudulent data. But The Chronicle has learned of yet another twist in the story.

According to one of the authors, Harvard University found that the study contained even more fraudulent data than previously revealed and it’s now asking the journal to note this new information. The finding is part of an investigation into a series of papers that Harvard has been conducting for more than a year, the author said.

Muzzled for years, vindicated MIT professor says fraud investigation into his lab did lasting damage

June 14, 2023

STAT: In the Lab

Damian Garde

For three years, nine months, and one week, Ram Sasisekharan lived under a gag order. In 2019, some of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor’s peers publicly accused his lab of falsifying research, setting in motion a lengthy internal investigation that sidelined his work, decimated his team, and barred him from speaking out in his own defense.

“The feeling was that we were guilty of something until we were proven innocent,” Sasisekharan, a decorated scientist whose work helped launch six biotech companies, said in an interview with STAT. “There were times I would wake up wondering if it had all been a nightmare.”

How Shoddy Data Becomes Sensational Research

Academics are addicted to p-hacking, data torturing, and other statistical sins.

June 6, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Gary Smith

Over the past 20 years, a wave of improbable-sounding scientific research has come under the microscope. Are Asian Americans really prone to heart attacks on the fourth day of every month? Do power poses really increase testosterone? Do men really eat more pizza when women are around? Are people named Brady really more susceptible to bradycardia (a slower-than-normal heart rate)? As early as 2005, alarm bells were going off over unrigorous social-science research — that was the year John P.A. Ioannidis, a Stanford professor of medicine, published “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” in PLOS Medicine. Since then, self-appointed “data thugs” have championed more transparent research practices, watchdog projects including the Center for Open Science and the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford have attempted to tackle the problem, and reproducibility efforts have gained steam in disciplines ranging from medicine to psychology to economics.

Welcoming codes of conduct

June 1, 2023

ChemistryWorld

Victoria Atkinson

The code of conduct is a staple of HR documentation. But in labs – filled with safety notices, instruction manuals and standard procedures – guidelines on the less practical aspects of research work are often curiously absent. Relying on assumed behavioural rules can be risky and many PIs are now choosing to explicitly outline their expectations, values and group procedures in public documents online.

For Lauren McKee, a glycoscientist at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden, creating and sharing her personal philosophy was a proactive and informal way to instigate a positive change within her group. ‘We call it the welcome document rather than the code of conduct so people have a positive mindset when they read it,’ she says. ‘It’s not prescriptive, but suggestive and encouraging. You won’t get into trouble if you don’t behave this way but it’ll be a great workplace if you do!’

Anonymizing peer review makes the process more just

Authors from richer, English-speaking countries gain unconscious boost when identified to referees, study finds.

May 26, 2023

Nature

Natasha Gilbert

When manuscript authors’ identities and affiliations are blocked from peer reviewers, unconscious bias is less likely to influence peer review than when that information is available, a study finds.

Fighting Claims of Research Misconduct, Stanford’s President Isn’t Pulling Punches

May 25, 2023

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Elissa Welle

Stanford University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne is in hot water.

Since last fall, allegations of image manipulation in scientific papers for which Tessier-Lavigne is listed as an author have spurred questions about his decades-long scientific career. While members of Stanford’s Board of Trustees and several outside legal and scientific experts review the claims of scientific misconduct, Tessier-Lavigne has remained at the helm of one of the world’s premier research institutions.

His unusual position as president-under-investigation mirrors an unusual public-relations approach. Instead of staying silent, as many embattled leaders do during an investigation, Tessier-Lavigne has vocally defended his actions, criticized the student newspaper in harsh terms, and cast himself as a faculty member first and president second.

Encourage whistle-blowing: how universities can help to resolve research’s mental-health crisis

Low pay, job insecurity, bullying and harassment all contribute to academic researchers reporting above-average levels of anxiety and depression. Institutions can improve working environments by looking at best practice elsewhere.

May 23, 2023

Nature

Editorial

Researchers working in academia are more likely to experience anxiety and depression than are members of the population at large, as we report in a Feature investigating the mental-health crisis in science. The COVID-19 pandemic has taken its toll on researchers, as it has on many in wider society, but it is clear that a major factor common in academia is a toxic work environment.

A proliferation of short-term contracts, low salaries (particularly for early-career researchers), competitive working environments and pressure to publish are all contributors — but so are bullying, discrimination and harassment. Study after study has reported on the devastating effects that these behaviours can have, especially on under-represented groups such as women, people of colour, low-income students and members of sexual and gender minorities.

Reporting research misconduct

When, how, and to whom

May 18, 2023

UKRIO: Research Integrity Office

Matt Hodgkinson

This guide, alongside our short guide to misconduct investigations, will support you in reporting suspected research misconduct and questionable research practices (QRPs) to institutions, publishers, and elsewhere, and to let you know what to expect from the process.

Fake scientific papers are alarmingly common

But new tools show promise in tackling growing symptom of academia’s “publish or perish” culture

May 9, 2023

Science

Jeffrey Brainard

When neuropsychologist Bernhard Sabel put his new fake-paper detector to work, he was “shocked” by what it found. After screening some 5000 papers, he estimates up to 34% of neuroscience papers published in 2020 were likely made up or plagiarized; in medicine, the figure was 24%. Both numbers, which he and colleagues report in a medRxiv preprint posted on 8 May, are well above levels they calculated for 2010—and far larger than the 2% baseline estimated in a 2022 publishers’ group report.

“It is just too hard to believe” at first, says Sabel of Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg and editor-in-chief of Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. It’s as if “somebody tells you 30% of what you eat is toxic.”

Support for those affected by scientific misconduct is crucial

May 8, 2023

Nature Human Behavior

Marret K. Noordewier

Cases of scientific misconduct can have a massive impact on scholars (especially junior scholars), and repercussions may last years. They need support, writes Marret K. Noordewier.

It was more than a decade ago that my PhD and postdoctoral advisor was caught committing scientific fraud1. His misconduct involved the fabrication of data that he shared with numerous collaborators, including me. Multiple investigations confirmed that he was the sole person responsible, and he was rightfully fired. Many of his collaborators were left to deal with the consequences. For me, as for others, these consequences were intense. Years of work were wasted, multiple papers were retracted and I had to deal with massive media attention, with committees and prosecutors investigating the fraud, and with my own questions about what had happened. I decided to pursue a second PhD. Not because it was required, but to ‘reboot’ my career and find my place in academia again.

How to improve scientific peer review: Four schools of thought

April 27, 2023

Wiley Online Library

Ludo Waltman, Wolfgang Kaltenbrunner, Stephen Pinfield, Helen Buckley Woods

Abstract

Peer review plays an essential role as one of the cornerstones of the scholarly publishing system. There are many initiatives that aim to improve the way in which peer review is organized, resulting in a highly complex landscape of innovation in peer review. Different initiatives are based on different views on the most urgent challenges faced by the peer review system, leading to a diversity of perspectives on how the system can be improved. To provide a more systematic understanding of the landscape of innovation in peer review, we suggest that the landscape is shaped by four schools of thought: The Quality & Reproducibility school, the Democracy & Transparency school, the Equity & Inclusion school, and the Efficiency & Incentives school. Each school has a different view on the key problems of the peer review system and the innovations necessary to address these problems. The schools partly complement each other, but we argue that there are also important tensions between them. We hope that the four schools of thought offer a useful framework to facilitate conversations about the future development of the peer review system.

How Do Scientists Perceive the Relationship Between Ethics and Science? A Pilot Study of Scientists’ Appeals to Values

April 25, 2023

SpringerLink

Caleb L. Linville, Aiden C. Cairns, Tyler Garcia, Bill Bridges, Jonathan Herington, James T. Laverty, & Scott Tanona

Abstract

Efforts to promote responsible conduct of research (RCR) should take into consideration how scientists already conceptualize the relationship between ethics and science. In this study, we investigated how scientists relate ethics and science by analyzing the values expressed in interviews with fifteen science faculty members at a large midwestern university. We identified the values the scientists appealed to when discussing research ethics, how explicitly they related their values to ethics, and the relationships between the values they appealed to. We found that the scientists in our study appealed to epistemic and ethical values with about the same frequency, and much more often than any other type of value. We also found that they explicitly associated epistemic values with ethical values. Participants were more likely to describe epistemic and ethical values as supporting each other, rather than trading off with each other. This suggests that many scientists already have a sophisticated understanding of the relationship between ethics and science, which may be an important resource for RCR training interventions.

NIH rules are supposed to stop ‘pass the harasser.’ In one recent case, they appear to have failed

Despite sending unwanted sexual emails and other “invasive” behavior, David Gilbert carried two NIH grants to a new institution and was awarded $2.5 million in new money

April 24, 2023

Science

Meredith Wadman

When genome researcher David Gilbert left Florida State University (FSU) in 2021 for the San Diego Biomedical Research Institute (SDBRI), he took two large National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants with him. The biomedical agency approved the transfer and went on to award Gilbert, a DNA replication expert who publishes in Science, Nature, and Cell, a new, $2.5 million grant last year.

None of this would be out of the ordinary—except that, in 2020, prior to any of these moves, FSU had completed a far-reaching investigation prompted when Gilbert emailed a description of his erotic dream to a graduate student. The probe revealed a yearslong history and concluded that Gilbert’s “gendered, sexualized and invasive behaviors were severe and pervasive.” NIH learned the full nature and extent of his misconduct at FSU before making the new award but after his move to San Diego—where his behavior elicited a new probe, Science has learned, and drove at least one woman scientist from the institute.

A Plagiarism Detector Will Try to Catch Students Who Cheat With ChatGPT

April 3, 2023

The Chronical of Higher Education

Eva Surovell

As faculty continue to debate how artificial intelligence might disrupt academic integrity, the popular plagiarism-detection service Turnitin announced on Monday that its products will now detect AI-generated language in assignments.

Turnitin’s software scans submissions and compares them to a database of past student essays, publications, and materials found online, and then generates a “similarity report” assessing whether a student inappropriately copied other sources.

The company says the new feature will allow instructors to identify the use of tools like ChatGPT with “98-percent confidence.”

Protecting the integrity of survey research

March 28, 2023

PNAS Nexus

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Arthur Lupia, Ashley Amaya, Henry E Brady, Rene Bautista, Joshua D Clinton, Jill A Dever, David Dutwin, Daniel L Goroff, D Sunshine Hillygus, Courtney Kennedy, Gary Langer, John S Lapinski, Michael Link, Tasha Philpot, Ken Prewitt, Doug Rivers, Lynn Vavreck, David C Wilson, Marcia K McNutt

Abstract

Although polling is not irredeemably broken, changes in technology and society create challenges that, if not addressed well, can threaten the quality of election polls and other important surveys on topics such as the economy. This essay describes some of these challenges and recommends remediations to protect the integrity of all kinds of survey research, including election polls. These 12 recommendations specify ways that survey researchers, and those who use polls and other public-oriented surveys, can increase the accuracy and trustworthiness of their data and analyses. Many of these recommendations align practice with the scientific norms of transparency, clarity, and self-correction. The transparency recommendations focus on improving disclosure of factors that affect the nature and quality of survey data. The clarity recommendations call for more precise use of terms such as “representative sample” and clear description of survey attributes that can affect accuracy. The recommendation about correcting the record urges the creation of a publicly available, professionally curated archive of identified technical problems and their remedies. The paper also calls for development of better benchmarks and for additional research on the effects of panel conditioning. Finally, the authors suggest ways to help people who want to use or learn from survey research understand the strengths and limitations of surveys and distinguish legitimate and problematic uses of these methods.

Trends in Extramural Research Integrity Allegations Received at NIH

March 22, 2023

NIH Extramural Nexus

Mike Lauer

At the start of the year, we briefly touched on our efforts to address research integrity violations in our 2022 Year In Review. Today we are sharing some more information on the overall trends in research integrity allegations associated with the NIH grants process. I want to note that while we are sharing these aggregate data, NIH does not discuss grants compliance reviews on specific funded awards, recipient institutions, or supported investigators, and whether such reviews occurred or are underway.

Our integrity portfolio broadened greatly around 2018 as professional misconduct became a major focus along with traditional scientific misconduct. Importantly, we also made concerted efforts with the research community over recent years to identify and address integrity issues.

AI makes plagiarism harder to detect, argue academics – in paper written by chatbot

Lecturers say programs capable of writing competent student coursework threaten academic integrity

March 19, 2023

The Guardian

Anna Fazackerley

An academic paper entitled Chatting and Cheating: Ensuring Academic Integrity in the Era of ChatGPT was published this month in an education journal, describing how artificial intelligence (AI) tools “raise a number of challenges and concerns, particularly in relation to academic honesty and plagiarism”.

What readers – and indeed the peer reviewers who cleared it for publication – did not know was that the paper itself had been written by the controversial AI chatbot ChatGPT.

“We wanted to show that ChatGPT is writing at a very high level,” said Prof Debby Cotton, director of academic practice at Plymouth Marjon University, who pretended to be the paper’s lead author. “This is an arms race,” she said. “The technology is improving very fast and it’s going to be difficult for universities to outrun it.”

Tormentor mentors, and how to survive them

Bad mentors can go absent, sap your energy or embroil you in their paranoia. Here are five tips for tackling a toxic relationship.

March 16, 2023

Nature: Career Column

Jennifer S Davila & Ruth Gotian

A mentor is the guide by your side who can help to develop your career, and cheer you on as you succeed and encourage you when you fail. But what happens when your mentor becomes uncooperative or resistant, or completely ghosts you by suddenly ending communication? Your mentor has now become a tormentor.

In a laboratory environment, the principal investigator is often a ‘mentor by default’ — which comes with the responsibilities of helping the trainee to develop professionally and paving a pathway for their future endeavours. Other mentors might include faculty members, postdoctoral colleagues and managers.

The repercussions of poor mentorship are far-reaching, from delayed career advancement to a trainee leaving science altogether.

Transparency in conducting and reporting research: A survey of authors, reviewers, and editors across scholarly disciplines

March 8, 2023

PLOS ONE

Mario Malički, IJsbrand Jan Aalbersberg, Lex Bouter, Adrian Mulligan, Gerben ter Riet

ABSTRACT

Calls have been made for improving transparency in conducting and reporting research, improving work climates, and preventing detrimental research practices. To assess attitudes and practices regarding these topics, we sent a survey to authors, reviewers, and editors. We received 3,659 (4.9%) responses out of 74,749 delivered emails. We found no significant differences between authors’, reviewers’, and editors’ attitudes towards transparency in conducting and reporting research, or towards their perceptions of work climates. Undeserved authorship was perceived by all groups as the most prevalent detrimental research practice, while fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, and not citing prior relevant research, were seen as more prevalent by editors than authors or reviewers. Overall, 20% of respondents admitted sacrificing the quality of their publications for quantity, and 14% reported that funders interfered in their study design or reporting. While survey respondents came from 126 different countries, due to the survey’s overall low response rate our results might not necessarily be generalizable. Nevertheless, results indicate that greater involvement of all stakeholders is needed to align actual practices with current recommendations.

How do we improve peer review?

February 28, 2023

Research Information

David Stuart speaks to experts in research integrity about some of the challenges facing peer review.

Peer review has evolved over the past 300 years to become the bedrock of today’s scholarly publishing system. When a researcher downloads an article from a reputable peer-reviewed journal, it is typically approached with a level of trust – the reader believes that it will have been validated by an expert in the same field as the original author.

Peer review is not perfect, and most scholars will have some personal experience of its limitations. Nevertheless, it is generally considered the best way we currently have to ensure the validity of research.

Escaping the predators

An over-reliance on publishing has left scientists prey to unscrupulous practices

February 17, 2023

Chemistry World

Bishwajit Paul

In Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll writes: ‘Humans are animals that like to write letters’. To paraphrase, ‘Scientists are animals who like to publish papers’. Or maybe it’s not that they like to, but because they have to. Early career researchers in particular are under constant pressure from the publish or perish culture of academia, where the metrics used to assess researchers primarily focus on number of publications rather than quality. It’s therefore not surprising that some academics fall prey to predatory publication practices.

Retracting my paper was painful. But it helped me grow as a scientist

February 16, 2023

Science

Jaivime Evaristo

My phone rang after I boarded a plane at the Amsterdam airport, on my way to visit family in the Philippines. It was my former Ph.D. adviser calling to tell me a preprint had just been posted that identified flaws in a paper we’d published in Nature looking at how forestry practices affect streamflow. My stomach dropped as he told me the authors of the critique were demanding a retraction. We couldn’t talk long—the plane soon took off. I spent the 16-hour flight processing a mix of emotions—disbelief, embarrassment, frustration—and wondering what this would mean for my career.

After the plane landed, I took out my laptop and logged onto the airport WiFi so I could read the critique for myself. It was harsh and thorough, pointing out several fundamental flaws in our methods and in the underlying data, which we’d gathered from other studies.

Leading Scientists Worldwide Are Victims of Fake Articles

They are planning legal action over pieces written with artificial intelligence.

February 10, 2023

Inside Higher Ed

Jack Grove for Times Higher Education

Leading international scientists who discovered articles written by artificial intelligence that have been published in their names have backed plans for legal action.

In recent months, academics at leading universities in Australia, Europe and North America have been alerted to low-quality scholarly articles—often little more than a page long, probably written by a language-scraping algorithm—appearing under their names in titles published by Prime Scholars, an open-access publisher registered to a west London address. That office, where hundreds of British companies are incorporated, is also home to other digital periodical companies whose authors are usually from India, the Middle East or developing economies.

Who should take responsibility for integrity in research?

February 2, 2023

LSE Impact Blog

George Gaskell, Nick Allum, Miriam Bidoglia, Abigail-Kate Reid

The journal Nature has in recent years featured hundreds of pieces on research integrity. To summarise, the current high-pace, hyper-competitive nature of research leads to threats to the quality and credibility of scientific research, notably through a reproducibility crisis, unreflective reliance on quantitative performance metrics, unreliable and biased peer review, falsification and fabrication. As such, Robert Merton’s idealised image of science as organised scepticism has been challenged by the irrational scepticism of right-wing extremism, religious bigotry, populism and absurd conspiracy theories.

ChatGPT Is Making Universities Rethink Plagiarism

Students and professors can’t decide whether the AI chatbot is a research tool—or a cheating engine.

January 30, 2023

Wired

Sofia Barnett

IN LATE DECEMBER of his sophomore year, Rutgers University student Kai Cobbs came to a conclusion he never thought possible: Artificial intelligence might just be dumber than humans.

After listening to his peers rave about the generative AI tool ChatGPT, Cobbs decided to toy around with the chatbot while writing an essay on the history of capitalism. Best known for its ability to generate long-form written content in response to user input prompts, Cobbs expected the tool to produce a nuanced and thoughtful response to his specific research directions. Instead, his screen produced a generic, poorly written paper he’d never dare to claim as his own.

“The quality of writing was appalling. The phrasing was awkward and it lacked complexity,” Cobbs says. “I just logically can’t imagine a student using writing that was generated through ChatGPT for a paper or anything when the content is just plain bad.”

Tools such as ChatGPT threaten transparent science; here are our ground rules for their use

As researchers dive into the brave new world of advanced AI chatbots, publishers need to acknowledge their legitimate uses and lay down clear guidelines to avoid abuse.

January 24, 2023

Nature

It has been clear for several years that artificial intelligence (AI) is gaining the ability to generate fluent language, churning out sentences that are increasingly hard to distinguish from text written by people. Last year, Nature reported that some scientists were already using chatbots as research assistants — to help organize their thinking, generate feedback on their work, assist with writing code and summarize research literature (Nature 611, 192–193; 2022).

But the release of the AI chatbot ChatGPT in November has brought the capabilities of such tools, known as large language models (LLMs), to a mass audience. Its developers, OpenAI in San Francisco, California, have made the chatbot free to use and easily accessible for people who don’t have technical expertise. Millions are using it, and the result has been an explosion of fun and sometimes frightening writing experiments that have turbocharged the growing excitement and consternation about these tools.

Multimillion-dollar trade in paper authorships alarms publishers

Journals have begun retracting publications with suspicious links to sites trading in author positions.

January 18, 2023

Nature

Holly Else

Research-integrity sleuths have uncovered hundreds of online advertisements that offer the chance to buy authorship on research papers to be published in reputable journals.

Publishers are investigating the claims, and have retracted dozens of articles over suspicions that people have paid to be named as authors, despite not participating in the research. Integrity specialists warn that the problem is growing, and say that other retractions are likely to follow.

Citing retracted literature: a word of caution

January 17, 2023

BMJ Journals: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine

Alessandro De Cassai, Francesco Volpe, Federico Geraldini, Burhan Dost, Annalisa Boscolo, and Paolo Navalesi

Abstract

Introduction Inappropriate citation of retracted literature is a common problem in the general medical literature. In 2020, more than 2300 articles were retracted, a dramatic increase from 38 in 2000. By exploring a contemporary series of retractions by one research group, we aimed to evaluate if citations of retracted articles is occurring in the area of regional anesthesiology.

Methods Using the Scopus database, we examined the full text of all the articles citing research articles coauthored by an anesthesiologist who had multiple articles retracted in 2022. After excluding the research articles citing non-retracted articles authored by the above mentioned anesthesiologist, we included in our analysis all the articles containing a retracted citation and published after the retraction notice.

Results The search was performed on October 30, 2022, retrieving a total of 121 articles citing the researcher’s work. Among the retrieved articles, 53 correctly cited non-retracted research and 37 were published before the retraction notice. Among the 31 remaining articles, 42 retracted research papers were cited. Twenty-five of the retracted articles were cited in the Discussion section of the manuscripts, 15 in the Introduction section, 1 in the Methods section (description of a technique), and one was cited in a review. No manuscript used the flawed data to calculate the sample size.

Discussion In this contemporary example from the regional anesthesia literature, we identified that citation of retracted work remains a common phenomenon.

Mistakes happen in research papers. But corrections often don’t

January 10, 2023

STAT

Amber Castillo

Mistakes happen — in life, in the lab, and, inevitably, in research papers, too. Journals use corrections and retractions to resolve those mistakes. But one particularly high-profile case is now drawing fresh attention to the problems with journals’ process for addressing concerns about research integrity.

Late last year, Stanford University announced that it was opening an investigation into its president, neuroscientist Marc Tessier-Lavigne, over allegations of research misconduct. Five studies co-authored by Tessier-Lavigne are now under the microscope for containing alleged altered images: a 1999 Cell study, a 2008 paper in the EMBO Journal, a 2003 Nature study, and two studies published in 2001 in Science.

Guest Post — Publishers Should Be Transparent About the Capabilities and Limitations of Software They Use to Detect Image Manipulation or Duplication

January 10, 2023

The Scholarly Kitchen

Mike Rossner

The STM Integrity Hub

Several posts (“The New STM Integrity Hub”, “Peer Review and Research Integrity: Five Reasons To Be Cheerful”, and “Research Integrity and Reproducibility are Two Aspects of the Same Underlying Issue”) in The Scholarly Kitchen last year described the STM Integrity Hub. This Hub is a platform being developed by STM Solutions, through which participating publishers will share access to their submitted manuscripts. The Hub will include software to detect each of the following: 1) The hallmarks of a manuscript produced by a paper mill; 2) simultaneous submission of a manuscript to multiple journals; 3) image manipulation/duplication. The software applications for the latter two are intended to work at scale, comparing the content of a submitted manuscript to thousands of other submitted manuscripts, and perhaps also to millions of published articles.

Is my study useless? Why researchers need methodological review boards

Making researchers account for their methods before data collection is a long-overdue step.

January 3, 2023

Nature

Daniel Lakens

Should researchers have the freedom to perform research that is a waste of time? Currently, the answer is a resounding ‘yes’. Or at least, no one stops to ask whether there are obvious methodological and statistical flaws in a proposed study that will make it useless from the get-go: a sample size that’s simply too small to test a hypothesis, for example.

In my role as chair of the central ethical review board at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, I’ve lost count of the number of times that a board member has remarked that, although we’re not supposed to comment on non-ethical issues, the way a study has been designed means it won’t yield any informative data. And yet we routinely wait until peer review — after the study has been done — to identify flaws that can’t then be corrected.