Seeing dementia clearly: UK collaboration uses advanced imaging to personalize care

Imagine being able to see the invisible—amyloid plaques, tau tangles, and metabolic changes in the living brain. This is no longer science fiction; it’s reality at the University of Kentucky. Thanks to a powerful collaboration between the University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown Center on Aging (SBCoA), UK Markey Cancer Center and the Department of Radiology, researchers are changing how Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are detected, understood and treated — bringing the future of precision medicine in this field to Kentuckians.

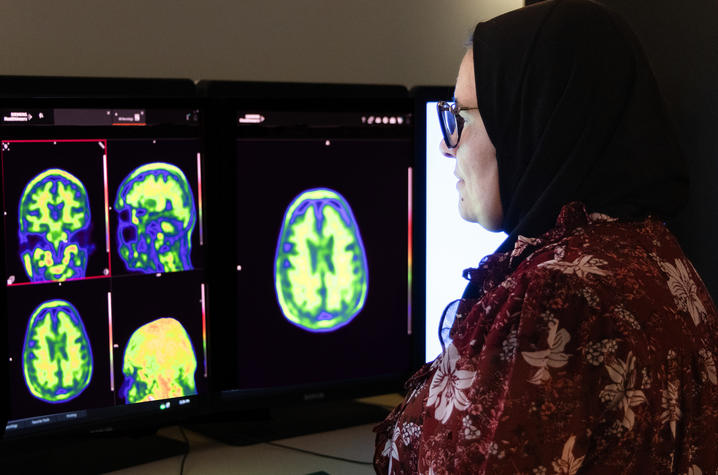

With leadership from neurologist Gregory Jicha, M.D., Ph.D., and radiologist Riham El Khouli, M.D., and in partnership with neuroscientist Brian Gold, Ph.D., co-director of UK’s Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy Center, the UK team is using state-of-the-art molecular positron emission tomography (PET) and MRI imaging to visualize the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease in living patients. These efforts are part of the National Institutes of Health-funded CLARiTI study, a national effort standardizing brain imaging across Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers to better understand the biological underpinnings of dementia.

“This really is revolutionary,” said Jicha, director of clinical trials at Sanders-Brown. “We’re now able to look inside the living brain and see amyloid and tau proteins, vascular injury and metabolic health — all in the same patient. It’s allowing us to personalize diagnosis and treatment in ways that were impossible before.”

Precision medicine comes to the brain

The approach mirrors a transformation that has already reshaped cancer care — one that Thomas Tucker, Ph.D., who recently retired as associate director for cancer prevention and control and senior director for cancer surveillance at Markey, knows well. An epidemiologist by training and a longtime leader at UK, Tucker sees the dementia imaging work as a natural extension of lessons learned in oncology.

“All science now is team science,” Tucker said. “This is a perfect example of how knowledge from one sector can really help and enlighten another. In cancer, molecular characterization changed everything. Now we’re seeing that same shift happen in dementia research.”

So just as the field of oncology transformed patient care through molecular diagnostics, the dementia team is applying these same principles. “Taking what we have learned and know from cancer … We can use it here too, right? Everything for precision of medicine, for each specific patient,” said El Khouli, who works within Markey. “We don’t have one thing we do for all patients like we used to do years ago. Now, every patient is different and with the molecular imaging, you can really have a disease print for that patient. You can then tailor and personalize their treatment management plan based on his molecular print.”

“I think it is safe to say this is kind of old school for Markey Cancer Center. They have been genotyping and molecularly characterizing tumors for a while, but this is truly a breakthrough in our field,” said Jicha. “We are taking lessons from cancer care through the years to shape this new philosophy for dementia diagnostics and treatment.”

While new blood tests have generated excitement as screening tools for Alzheimer’s, Jicha noted that they can only “rule out” the disease. For confirmation, patients need molecular imaging — and that’s where UK’s collaboration shines. Through fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scans alongside advanced MRI, researchers can pinpoint exactly what is driving cognitive changes. Fluorodeoxyglucose is a radioactive sugar used during these scans to help show how tissues and organs are functioning.

In some cases, these scans reveal that symptoms thought to be Alzheimer’s stem from a different cause entirely. “One of our CLARiTI participants looked like an Alzheimer’s case, but imaging told a different story,” Jicha said. “The FDG PET showed a frontotemporal pattern, the amyloid PET was negative and the tau PET was positive in the frontal and temporal lobes — confirming frontotemporal dementia. That completely changed how we approached that patient’s care.”

For Tucker, the power of imaging is not just scientific; it’s personal. His wife was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease more than two years ago and is now being treated at Sanders-Brown.

“She’s on one of the new anti-amyloid therapies, and she’s doing remarkably well,” Tucker said. “Her cognitive function hasn’t progressed the way we feared — in some ways, it’s even improved. That wasn’t something we expected.”

Another advantage of the advanced imaging is that it can help identify which patients are most likely to benefit from therapies, sparing others from unnecessary treatment while accelerating care for those who stand to gain the most.

“Without imaging, everyone goes on therapy and you hope for the best,” Tucker said. “With imaging, you can be much more precise — and that’s a huge advantage for patients and families.”

Expanding access, increasing capacity

Demand for these advanced scans is soaring. “We’re now doing four to five amyloid PET cases a day, and we have a huge backlog because of the demand,” said El Khouli. “We’re even exploring dedicated brain PET scanners to expand capacity. These would allow us to handle both research and clinical patients more efficiently.”

El Khouli said she and her team are also evaluating new digital PET scanners and software upgrades to ensure the highest image quality possible. “Our value comes from our collaboration,” said El Khouli. “We work hand-in-hand with Sanders-Brown and Markey Cancer Center, keeping our imaging equipment and radiopharmaceuticals state-of-the-art to meet the needs of patients and researchers.”

Partnership at the core

UK’s multidisciplinary environment is what each researcher believes makes this work possible. “We couldn’t do the developmental research studies that bring this imaging to life without Radiology,” Jicha said. “Very few centers nationally have this level of capability — particularly for tau PET scanning.”

“Our progress depends on collaboration. Radiology can’t advance without our partners in neuroscience, and Sanders-Brown can’t advance without Radiology. Together, we make each other better — and our patients benefit most of all,” said El Khouli.

“The university isn’t the buildings — it’s the people,” said Tucker. “What’s happening between Sanders-Brown, Radiology and Markey is exactly how meaningful scientific progress happens.”

Changing the conversation

For patients and families, molecular imaging offers something many have been searching for: clarity.

“People come to us after visiting multiple medical centers where they were simply told, ‘You have some form of dementia,’” Jicha said. “That’s not good enough for us. Families deserve to know what’s causing it and what can be done.”

That need for clarity is one Tucker understands firsthand. After decades as a cancer researcher and academic leader, he now holds the role as a full-time caregiver — a transition he describes as both profound and deeply meaningful.

“To watch someone you love lose pieces of their mind is devastating,” Tucker said. “If this science can prevent that in some cases — or even delay it — that’s incredibly powerful. For me, being able to support my wife through this isn’t a burden. It’s an honor.”

Jicha has seen time and again how this level of insight transforms the patient experience. “When I can show a patient the amyloid buildup in their brain — or the absence of it — it changes everything,” he said. “It brings understanding, relief and direction. Just as cancer treatment has evolved from a one-size-fits-all approach to personalized, molecular-based therapies, dementia care is now entering that new era of precision medicine. Every patient is different — and with this technology, we can finally treat them that way.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01AG082350. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.